What role did churches play in the civil war?

Why were so many churches desecrated during the civil war and what part did Cromwell play in this?

Many church buildings were caught up in the fighting during the English civil war, either by accident or design. Churches were solid, stone-built structures, in the seventeenth century often one of the few stone structures which stood in small settlements, many had fairly narrow windows set quite high in the outer walls, they generally possessed a lofty tower which looked down on the surrounding land and community and they stood within graveyards which were often enclosed by a circuit of solid stone walls. As such, they had considerable military potential, as offensive or defensive positions, fortified and held as part of a planned and long-term operation or on a short-term basis by troops who had unexpectedly come under attack. The graveyard and the church within it could be occupied and held and the church tower made an excellent vantage point not only for observing the surrounding area but also for firing down on enemy positions; both musketeers and artillery could be positioned within the tower and on the roof.

Many church buildings were caught up in the fighting during the English civil war, either by accident or design. Churches were solid, stone-built structures, in the seventeenth century often one of the few stone structures which stood in small settlements, many had fairly narrow windows set quite high in the outer walls, they generally possessed a lofty tower which looked down on the surrounding land and community and they stood within graveyards which were often enclosed by a circuit of solid stone walls. As such, they had considerable military potential, as offensive or defensive positions, fortified and held as part of a planned and long-term operation or on a short-term basis by troops who had unexpectedly come under attack. The graveyard and the church within it could be occupied and held and the church tower made an excellent vantage point not only for observing the surrounding area but also for firing down on enemy positions; both musketeers and artillery could be positioned within the tower and on the roof.

There are many examples of churches being used in these ways during the civil war. Churches could play a role in urban warfare. For example, in the closing days of 1643 Sir William Waller captured the town of Arundel, West Sussex, and occupied St Nicholas’s church in order to use the tower as a vantage point from which to bombard Arundel castle. The operation was successful, for in early January the royalist garrison surrendered the damaged fortress. With less success, Sir John Byron’s royalists had occupied another St Nicholas’s church, in Nottingham in autumn 1643, to bombard Nottingham castle from guns mounted in the tower. The castle proved impregnable, but not so the church, which was badly damaged in John Hutchinson’s counter-bombardment and was then deliberately demolished to prevent its use in any future royalist attack. Having overrun the town of Scarborough in summer 1644, the parliamentarians mounted a year-long campaign against the castle, still in royalist hands, using St Mary’s church as one of their principal batteries. The church was badly damaged by the royalist counter-bombardment which destroyed parts of the building and which probably contributed to the collapse of the main tower in the 1650s. In autumn 1645, during the closing stages of the protracted parliamentary siege of royalist-held Chester, Sir William Brereton occupied St John’s church, a Norman edifice just outside the walled city, and from its tower bombarded the adjoining stretch of wall. The vibrations caused by heavy artillery being discharged within the medieval structure may have weakened it, for the old tower of St John’s suddenly collapsed in the nineteenth century. As well as a large number of town churches, a small number of cathedrals were caught up in struggles to control and hold important towns, most notably the cathedral in Lichfield, Staffordshire, which was badly damaged when the town changed hands twice amidst heavy fighting in the course of 1643.

Many suburban churches perished during the civil war, deliberately demolished by the garrison defending a major town as part of the much larger process of clearing and flattening the ground outside the principal defended area, so providing a clear field of fire and denying shelter and vantage points to any attacking or besieging force. This process was undertaken (in whole or in part) around many fortified towns during the war, including Bridgwater, Bristol, Chester, Exeter, Gloucester, Kingston upon Hull, London, Newark, Newcastle upon Tyne, Oxford, Plymouth, Shrewsbury and Worcester. Stone churches were far more difficult to clear than timber or timber-framed houses, which could be easily fired, and they generally required greater effort. The demolition of churches outside the defensive lines could be quite methodical, with the stone and timber carefully salvaged for reuse in strengthening the town’s defences. Moreover, there are plenty of examples of church bells, organ pipes, lead roofing and fittings and even lead coffins being stripped out and then melted down to make bullets and other items of arms and ammunition.

Many churches in much smaller, semi-rural communities were also badly damaged during the war because they became caught up in attacks upon adjoining fortified houses which had been garrisoned by one side of the other. Examples include the churches at Boarstall in Buckinghamshire, Brampton Bryan in Herefordshire, Woolsthorpe in Lincolnshire, Faringdon in Oxfordshire, Stokesay and High Ercall in Shropshire and Compton Wynyates in Warkwickshire.

Fairly isolated, village churches could serve as military strong-points in their own right, guarding key locations. For example, All Saints’ church in Crondall, Hampshire, was a minor parliamentary outpost for much of the war, guarding the western approaches to Farnham, while the royalists similarly fortified and garrisoned the surviving buildings of Thurgarton Priory in Nottinghamshire as a minor outpost of their stronghold of Newark from December 1642 until December 1644, when the buildings were stormed and captured by parliamentarians.

In emergency, troops might fall back on a church (and surrounding churchyard) and try to hold out there. For example, in December 1643 Sir William Waller launched a surprise attack on Alton in Hampshire, and much of the outnumbered royalist foot fell back on St Laurence’s, seeking first to hold the churchyard and then, when forced further back, to defend the church itself. Stiff resistance continued even after some parliamentarians had forced their way into the church and only when the royalist leader, Colonel Bolle, was cut down, did the surviving royalists surrender. Marks in the door and on the stone walls and pillars supposedly bear witness to civil war pikes and bullets. In August 1644 some royalist soldiers were caught in Lostwithiel, Cornwall, as the Earl of Essex’s army marched into the town, and they tried to hold out in St Bartholomew’s church. Resistance was short-lived, for the parliamentarians set off barrels of gun-powder by the church to flush them out, in the process lifting off part of the roof.

Churches could serve as magazines, sometimes with disastrous consequences. For example, the battle of Torrington in Devon in February 1646 ended when royalist gun-powder stored in St Michael’s was set off by accident or design, resulting in a huge explosion. In a similar vein, St Peter Mancroft’s church in Norwich was badly damaged when the magazine in the nearby Committee House ignited during the royalist riots of May 1648.

Churches could serve as prisons. After the collapse of the Scottish-royalist invasion of summer 1648, surviving Scottish soldiers were held prisoner in a number of churches in the North West. In May 1649 Fairfax and Cromwell crushed a mutiny at Burford in Oxfordshire and briefly imprisoned the rebellious troops in St John’s church; the font still faintly bears the inscription made by one of them – ‘Anthony Sedley 1649 Prisner’.

Churchyards or even churches themselves could also serve during the civil war as places of execution or worse. Thus when Captain Steel was condemned for having surrendered Beeston castle in Cheshire to the royalists too easily in December 1643, he was executed by firing squad in Nantwich churchyard. Similarly, three ringleaders of the May 1649 mutiny were executed by firing squad in the churchyard of St John’s church in Burford. Even darker events took place in St Bartoline’s church, Barthomley, Cheshire, the site of one of the most notorious massacres of the civil war. When, in December 1643, royalist forces under Sir John Byron swept into the village, a group of about twenty locals sought sanctuary in the church tower, only to be smoked out by the royalists, who made a bonfire of pews and benches at the foot of the tower, and then to be put to the sword by the royalists. Twelve were killed on the spot, and many of the remainder were badly wounded.

Only on a handful of occasions was Oliver Cromwell directly and personally involved in military action against opponents who had fortified and were defending churches. In April 1643, in one of his first major actions, Cromwell attacked and overwhelmed royalist forces who had occupied and fortified the small town of Crowland or Croyland in south Lincolnshire, and who were using as their main base the church and other surviving sections of the medieval abbey. Nearly a year later, in March 1644, he attacked and captured Hillesden House in Buckinghamshire. The adjoining All Saints’ church was probably being held as an outpost of the main house and marks in the church door are supposedly bullet holes made as Cromwell’s men captured the church. In June 1645 Cromwell bombarded and stormed St Michael’s church at Highworth in Wiltshire, garrisoned by royalists in 1644 and fortified by them by adding outer earthwork defences. Cromwell’s unhappy connections with Burford church in spring 1649 have already been noted.

As well as the accidental or deliberate damage to churches in the course of the fighting and due to purely military factors, many parliamentarians also sought for ideological and religious reasons to alter the fabric and fittings of churches, to remove and destroy physical elements and symbols which they associated with Roman Catholicism or with the high church, Laudian policies pursued by Charles I and his Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, during the pre-war period; for many opponents of these policies, Laudianism was effectively creeping Catholicism. Targets of this ‘iconoclasm’ included altar rails (many of them very recently installed), altars, stained glass, paintings on screens, the screens themselves, religious statues and carvings, crosses, vestments, prayer books and organs; around the same time, though not principally for religious reasons, royal arms and the tombs and effigies of some elite families were also sometimes damaged or defaced. Some of this religiously-motivated destruction was undertaken in a fairly methodical way, with campaigns of purification run during the mid 1640s in line with parliamentary policies and ordinances and overseen by mayors and aldermen or by semi-official commissioners – the best known and best recorded example of this type of iconoclasm is the work of William Dowsing in East Anglia. However, much of it was far more ad hoc and spontaneous, undertaken by members of local communities, especially in the early 1640s, beginning at the time of the Scots wars and thus before the English civil war itself had broken out.

Much of this destruction of church fabric and fittings was undertaken or overseen by civilians, ranging from local rabbles to civic officials, but some of it undoubtedly was caused by soldiers, by troops raised to fight for the king in the second Scots war of 1640 as well as by parliamentary troops from 1642 onwards. Royalists loved to recount, if not to exaggerate or to invent, examples of excesses by parliamentary troops – accounts of obscene parodies of religious ceremonies in which animals were baptised, of soldiers urinating in fonts or dressing up in holy vestments, of statues of Christ and carved angels in the roof being used for target practice, and so forth. In the course of the civil wars, parliamentary soldiers certainly did damage a number of religious buildings, in some cases with a clear anti-Catholic, religious intent, in line with the broader iconoclastic campaign of the 1640s, but in other cases apparently indulging in wanton destruction or in search of plunder. There is fairly well-documented evidence of damage caused by parliamentary troops to Canterbury, Chichester, Exeter, Gloucester, Lichfield, Lincoln, Peterborough, Rochester, St Paul’s, Winchester and Worcester cathedrals and to a few dozen parish churches.

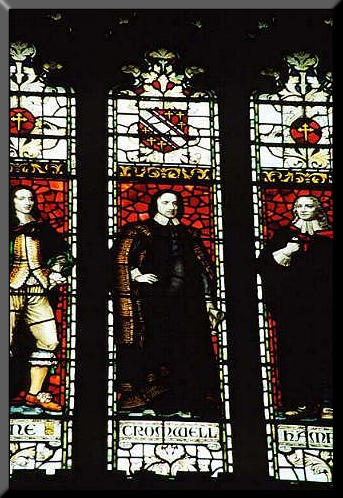

However, despite the many myths and folk tales, both iconoclasm and wanton destruction at the hands of soldiers and civilians during the 1640s need to be put into perspective. The destruction of rood screens and rood lofts, of religious statuary and paintings and painted glass which undoubtedly did occur then is dwarfed by the iconoclasm of the earlier Reformation, by the extensive destruction undertaken from above and from below during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and Elizabeth I as the English Reformation was launched and relaunched and as Protestantism overwhelmed Catholicism and became embedded in England and Wales. Furthermore, little or no iconoclasm can reliably be attributed to Oliver Cromwell himself or to troops under his direct and personal command. Even historians generally hostile to him and his cause struggle to find clearly-documented, contemporary accounts of Cromwell personally indulging in the purification or desecration of churches. Many stories along these lines, such as tales that Cromwell climbed ladders and personally smashed crucifixes or that he undertook a campaign of breaking painted windows, often first emerged decades or even centuries after Cromwell’s death and, finding no contemporary corroboration or support, are probably unreliable. There survives just a handful of strictly contemporary accounts linking Cromwell in person to iconoclasm – for example in 1647 a royalist newspaper claimed that during the civil war Peterborough cathedral had been ‘robb’d, defac’d and spoyl’d by Cromwel’, who smashed the west window, demolished the choir loft and destroyed the service books – but these sources, displaying strong anti-Cromwellian and anti-parliamentarian biases, are generally treated with scepticism by modern historians who have specialised in this area. There is no doubt that someone called Cromwell was responsible for unleashing and encouraging an extensive campaign of iconoclasm which altered the fabric and appearance of thousands of churches in England and Wales, but that was Thomas Cromwell, chief minister to Henry VIII at the time of the Henrician Reformation, not Oliver Cromwell a century or more later. As James Waylen put it pithily and colourfully in the late nineteenth century:

But not only the capture of bells, but every other form of church-spoilation, wherever found in England, is habitually attributed to the personal agency of Cromwell. All else is forgotten but the destroying maul of this fabulous giant, whose solitary hobgoblin figure looming out of the dark ages, has put all other spoilers to flight. Of which indeed we may say that it is a doctrine so long and so firmly fixed in the sexton-mind as to be fairly excusable in a parochial cicerone; but it is not so excusable in other official persons of clerical grade, who ought to know better, but who make it a part of their religion to nurse the prejudice. It was rather the previous age, namely that of the Reformation, which witnessed these defacements.