What happened to Cromwell’s body after his death? Where are his mortal remains now?

“It is extraordinary to see to what an height the passions of men are carried even about trifles – to see how they have tortured their imaginations to contradict their reason; with respect to the disposal of Oliver’s corpse, his friends cannot unfortunately agree amongst themselves in what way the body of the Protector was disposed of.”

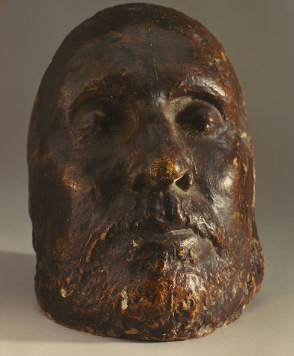

Cromwell’s death mask

Oliver Cromwell died at Whitehall on the afternoon of Friday, 3 September 1658. At the direction of the Council, the corpse was embowelled and embalmed on the following day. Thereafter the physical remains effectively disappeared from public view and both the elaborate lying in state at Somerset House during October and early November and the grand state funeral through London on 23 November centred on a (probably empty) coffin and on one or more life-size models or effigies.

It was assumed that the corpse had been quietly interred before 23 November somewhere within Westminster Abbey, probably at the spot near the east end of Henry VII’s Chapel over which the hearse and recumbent effigy were placed at the conclusion of the state funeral. In autumn 1660 parliament ordered the exhumation and posthumous execution of several regicides and in January 1661 Westminster Abbey was searched for the remains of Cromwell, Henry Ireton and John Bradshaw. Three corpses were duly produced and conveyed to Tyburn, where they were hanged and then decapitated on 30 January, the twelfth anniversary of Charles I’s execution. The heads were displayed on poles above Westminster Hall. The three headless corpses, including the supposed trunk of Oliver Cromwell, were simply dumped at dusk in an unmarked pit beneath Tyburn gallows.

Doubts over the true location of Cromwell’s remains were raised at the time and are not merely the fruit of Georgian and Victorian fancy. By the mid 1660s reports were circulating that the Protector had transposed the royal tombs in Westminster Abbey to conceal the site of his own grave so that the body exhumed in 1661 may not have been his. The story first appeared in print in 1664 when Pepys discussed the matter with Cromwell’s former chaplain. The uncertainty and the imaginative tales it engendered probably originated in the speed with which Cromwell’s corpse had disappeared from public view in 1658. Unfortunately, contemporary reports of the handling and disposal of the body are vague and the vocabulary misleading. Newspapers and pamphlets used the terms ‘corpse’ and ‘body’ as well as ‘effigy’ – often in their plural forms – in a haphazard and apparently interchangeable fashion and in circumstances in which the actual mortal remains were certainly not intended. Nonetheless, it is clear that what was on show in Somerset House in October and November 1658 was not the corpse itself but a moveable effigy, crafted in wood and with a wax face and features. Neither the detailed description of the lying and standing in state carried by many newspapers and pamphlets nor the crude woodcut of the scene reproduced in Some Further Intelligence gives any indication of the whereabouts of the mortal remains. The body may have been stored in Somerset House for a time, but it was never displayed and was probably not within the apartments open to the public during the lying in state. Similarly, the state funeral centred on an effigy, and several commentators specifically reported that Cromwell’s corpse was not present that day, ‘his actual body having been buried privately many weeks ago’.

The reason for the speedy disappearance and premature burial of the corpse is revealed by George Bate, one of the physicians summoned to embalm the remains on 4 September. Writing around the time of the Restoration, Bate relates that although Cromwell’s corpse was duly embowelled

“…and his Body filled with Spices, wrapped in a fourfold Cerecloath,…put first into a Coffin of Lead, and then into a Wooden one, yet it purged and wrought through all, so that there was a necessity of interring it before the Solemnity of his Funerals.”

Although there exists no other contemporary medical statement to corroborate it and despite the anti-Cromwellian bias evident in much of Bate’s account, there seems no strong reason to doubt Bate’s account of an unsuccessful embalming, leaving the corpse unfit for public display and necessitating speedy interment. Bate mentions neither the date of the burial – he does not claim that interment immediately followed the events of 4 September – nor the location.

The newssheets and other commentators noted that on the evening of 20 September Cromwell’s ‘corps’ was conveyed from Whitehall to Somerset House ‘in a private manner, being attended only by his servants’. Several private correspondents reported that seven weeks later, on 10 November, the ‘corpses’ or ‘body’ was carried from Somerset House, through St James’s Park to Westminster Abbey ‘and there interred in a Vault in Henry the Seventh’s Chapel’. The ambiguities of vocabulary permit several interpretations. Decomposition could have set in quite quickly, necessitating interment soon after death, probably sometime during September. Alternatively, decay could have been checked or disguised for several weeks by the spices, cerecloth, lead sheets and wooden coffin and the corpse may not have been buried until 10 November – a seventeenth-century lying in state often featured an effigy rather than the body itself and the latter’s absence from the public display in Somerset House in October and early November is no proof that it had been buried by then. But whatever the detailed timetable of its movements, there is little doubt that Cromwell’s corpse was interred without show in Westminster Abbey sometime between 4 September and 23 November 1658. In April 1659 Samuel Carrington, the best of Cromwell’s early biographers, described how the corpse had been buried ‘some dayes before’ the state funeral ‘in Henry the Seventh’s Chappel in a Vault purposely prepared’.

Speculation surrounding the identity of the corpse produced at Tyburn in January 1661 rests upon lingering doubts over the location of the Protector’s grave, and particularly upon rumours that Cromwell had transposed the royal tombs. The most colourful version, in which Cromwell directed that his corpse be exchanged with that of Charles I, has a horrified executioner discovering at Tyburn that the hanging body had already been decapitated and the head sewn back, whereupon proceedings were brought to a hurried and understandably embarrassed halt. The tale, first aired in the mid-eighteenth century, rests upon no contemporary evidence and is quite inconsistent with contemporary accounts of events at Tyburn. Moreover the remains of Charles I have since been discovered undisturbed at Windsor. More recently, in the 1930s, the meagre contemporary evidence was employed to dramatic ends by F J Varley, who contended that the Protector was not buried in Henry VII’s Chapel – alternative sites were not explored – and that the masons found merely an empty coffin when they opened the vault in January 1661. Ireton’s grave, too, was empty, Varley suggested, for the Lord Deputy had died in Ireland in 1651 of plague or a plague-like disease and in such circumstances the infected corpse would not have been embalmed and carried to London for burial. Nothing daunted, the authorities found two other bodies in suitable condition and the act of public vengeance went ahead at Tyburn with a couple of substitute corpses. Varley rightly pointed out that most of the surviving accounts of the exhumations and executions, including those of the newssheets, Evelyn, Pepys, Wharton and perhaps Rugg, too, were written by people not present in person. Of the few eye-witness accounts, Peter Mundy relates that the corpses of Cromwell and Ireton were ‘wrapped in searcloth’ and a manuscript by Edward Sainthill, now lost, revealed that Cromwell was hanged ‘in a green seare cloth, very fresh embalmed’ and carried a drawing of the scene in which ‘Cromwell is represented like a mummy swathed up, with no visible legs or feet’. Thomas Rugg, who may have been another eye-witness, noted that Cromwell and the others were hanged ‘in their shrouds’. The implication is that the corpse was kept shrouded throughout so that the substitution should not be detected.

But against this must be placed very strong indications that Cromwell’s body was, in fact, exhumed and executed in 1661. There is the practical point that the face would have been uncovered and (depending upon the state of decomposition) may still have been recognisable when the corpse was cut down and beheaded at the end of the day. Moreover, there are at least two apparently contemporary descriptions of the successful search for Cromwell’s tomb in Westminster Abbey. The first, printed in the mid-eighteenth century from a much earlier manuscript, relates how the body was found in a vault ‘in the middle Isle of Henry the Seventh’s Chapel, at the east end’; an engraved copper plate bearing the name and arms of the Protector was found on the corpse and was pocketed by the Serjeant of the House. The second account, supposedly passed down by Serjeant Norfolk himself, describes how the body was with difficulty recovered from a number of lead and wooden cases cemented together into a wall in the abbey; again, there is reference to the ‘gold gorget’ found resting on the corpse. The inscribed plate, together with a mason’s receipt for 15 shillings ‘for taking up the corpses of Cromwell and Ireton and Bradshaw’, was still extant in the late eighteenth century and examined and described by Noble and others.

Although some doubt must remain, there is, then, strong if not overwhelming evidence to suggest that Cromwell was quietly interred in Henry VII’s Chapel in autumn 1658, that his tomb was successfully located and opened in January 1661 and that the body displayed and dumped at Tyburn was, indeed, his. This was the line accepted and followed by historians during the half century or more after Cromwell’s death. For instance, The Perfect Politician of 1660 reported without a hint of doubt or controversy that Cromwell had been buried in Westminster Abbey, and a year later the author of Short Meditations on…the Life and Death of Oliver Cromwell was equally satisfied that the arch-traitor ‘hath now no other Tombe but a Turf under Tyburn’. Heath, Dugdale, Burton, Eachard and Dart each told a straightforward tale of burial in Westminster Abbey and exhumation and reburial at Tyburn, though enriched with elaborations of their own. They particularly enjoyed dwelling upon the unsuccessful embalming, heightening Bate’s account with lurid and probably imaginary tales of Cromwell’s own natural ‘corruption and filth’ and of the corpse fermenting ‘after such an unheard of manner, that it burst all in pieces’. In the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century successive editions of the Register of the Burials at Westminster Abbey described the area near the east end of Henry VII’s Chapel as ‘Oliver’s Vault’ in the clear belief that the Protector had once lain there. Tyburn via Westminster Abbey had become widely accepted as the twin resting places of Oliver Cromwell.

Acceptance of the Westminster and Tyburn account was, however, never quite total and others survived in oral or manuscript form to find their way into print, and thus to reach a much wider audience, in the eighteenth century. The two most prominent were recorded in print for the first time by White Kennet in 1728. Kennet closely followed Dugdale, Dart, et al with a standard account of burial, exhumation and final disposal in ‘a deep hole under the Gallows’. But at this point he added a crucial marginal note:

Many have since reported, that Cromwell’s body was not buried at Westminster but by his own Order, to prevent any insult upon it, was either in a leaden coffin cast into the Thames; or carried to his place of Victory in Naseby field.

In 1730 the first of these two tales was related in full by John Oldmixon, who claimed to have heard it forty years before from a ‘religious’ and ‘reliable Gentle-woman who attended Cromwell in his last sickness’.

She told me that the Day after Cromwell’s death, it was consulted how to dispose of his Corpse. They could not pretend to keep it for the Pomp of a publick burial. Among other proposals this was one, that considering the Malice, Rage and Cruelty of the Cavaliers, it was most certain, they who never spar’d either Living or Dead in the Lust of their revenge, would insult the body of this their most dreadful enemy, if ever it was in their power; and to prevent its falling into such barbarous hands, it was resolved to wrap it up in lead, to put it aboard a Barge, and sink it in the deepest part of the Thames, which was done the night following; two of his near relations, and some Trusty soldiers, undertaking to do it.

In 1742 the Harleian Miscellany published a manuscript, now lost, allegedly drawn up by or for the son of the regicide John Barkstead, who claimed that his father had consulted Cromwell during his last sickness ‘to know where he would be buried’.

To which he answered, Where he had obtained the greatest Victory and Glory and as nigh the Spot as could be guessed where the Heat of the Action was viz. in the Field at Naseby, Co. Northampton, which accordingly was thus performed: At Midnight (soon after his death), being first embalmed and wrapped in a leaden coffin, he was, in a Hearse, conveyed to the said field, the said Mr Barkstead, by Order of his father, attending close to the Hearse; and, being come to the field, there found, about the Midst of it, a Grave, dug about nine feet deep, with the green sod carefully laid on one side, and the Mould on the other; in which, the Coffin being soon put, the Grave was instantly filled up, and the green sod laid exactly flat upon it, care being taken that the surplus Mould was clean taken away. Soon after, like care was taken that the said Field was intirely ploughed up, and sown three or four years successively with Wheat.

The story received rather dubious corroboration in the nineteenth century with the publication of a memorandum of a discussion between the Rev. Marshall of Naseby and Oliver Cromwell of Cheshunt (died 1821), the last direct male descendant of the Protector. The younger Cromwell retold a story passed to him from his mother, who in turn had it from an aged servant who in his youth had served Richard Cromwell. This servant recalled that shortly after Oliver’s death

“…the corpse was brought through Cheshunt in the night; and that horses were ordered to be in readiness to convey it down to Huntingdon, to which place he went himself to assist in attending the horses and to bring them back; and that the corpse did not remain in Huntingdon but was carried on much further.”

Still more suggestions followed. In 1787 John Prestwich asserted that the Protector’s remains ‘were privately interred in a small paddock near Holborn, in that very spot over which the obelisk is placed in Red Lion Square, Holborn – The Secret!’ No authority was cited in support nor did Prestwich indicate whether burial took place in autumn 1658, soon after death, or in January 1661, with the exhumed corpse rescued en route to Tyburn and hurriedly interred nearby to save it from further indignity – the remains of Cromwell and Ireton were taken to the Red Lion Inn on 28 or 29 January before the final journey to Tyburn. In 2000, as part of his full-length re-examination of the causes of Cromwell’s death and the circumstances surrounding it, Professor H F McMains also came out in favour of a Red Lion Square reburial. He argued that Cromwell’s body was successfully located and exhumed but was then substituted for another corpse while stored at the Red Lion Inn in Holborn and secretly reburied nearby. Although he adduced no new, hard evidence to support this tale, Professor McMains went on to speculate that both Milton and Marvell may have taken the lead in the switch, assisted by a medical student, who found a substitute body, and abetted by the officer in charge, who was bribed.

In 1809 a correspondent of the European Magazine repeated a story related to him by Dr Cromwell Mortimer, a distant descendant of the Protector, which had allegedly been handed down through the family since the seventeenth century, that on Cromwell’s instructions his body was

“…enclosed in a strong plain oak coffin, without any name or inscription, and buried twenty feet deep in a field on his paternal estate in Huntingdonshire and the field…afterwards ploughed up.”

The account is rendered all the more implausible by being linked to the old story of how the corpse planted in Westminster Abbey and then exhumed was discovered at Tyburn to have already been decapitated and the head reattached. Nonetheless, several later writers repeated the story, citing an old and conveniently vague family tradition that the Protector had been buried on or near his estates around Huntingdon.

A further three possible burial sites were proposed in the nineteenth century, namely tombs in St Nicholas’s church, Chiswick and St Andrew’s church, Northborough and a stone vault in Newburgh Priory. In each case, the story originated in quite genuine Cromwellian connections. Cromwell’s daughter, Mary, Lady Fauconberg, had connections with Chiswick and both she and her sister, Frances, lie somewhere in St Nicholas’s church. Another daughter, Elizabeth, and her husband John Claypole owned Northborough manor and several of their children, together with the Protector’s widow, were buried in St Andrew’s. Newburgh Priory was once the country home of Lord and Lady Fauconberg. Despite protestations to the contrary – for example, in the late nineteenth century the Cromwellian scholar James Waylen strongly supported the claims of Newburgh, describing them as ‘not a legend but a genuine piece of family history’ – in reality no contemporary evidence links Cromwell’s burial with all or any of these sites, and each story first appeared in print more than two centuries after the Protector’s death. To their credit, Victorian correspondents quickly scuppered an equally spurious suggestion that Cromwell was buried somewhere in Abney Park cemetery.

From 1640 Cromwell lived and acted on a series of public stages, first in the House of Commons then the battlefield, later undertaking all the duties incumbent upon his office of Protector. But on 3 September 1658 the public life ended and his mortal remains disappeared from view with an abruptness which some considered unusual, even suspicious. The speedy removal of the corpse from public gaze and its private and premature burial gave rise at the time to speculation, not that Cromwell was still alive – no-one seems seriously to have doubted the fact of his death – but that he had been interred somewhere other than the designated vault in Henry VII’s Chapel, Westminster Abbey. Later generations magnified the suspicions and constructed from them a number of imaginative tales leading to a series of graves stretching from London to Yorkshire. In each case the reason for the alleged secret burial was the desire of the Protector himself or of his friends to preserve the body from future mutilation by royalists and other enemies. The hasty and rather furtive disposal of the body in 1658 and the paucity and ambiguous vocabulary of contemporary accounts do leave a grain of doubt, but the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that Cromwell was buried in Henry VII’s Chapel, that his remains were located, exhumed and posthumously executed in January 1661 and that his headless trunk was dumped in a pit at Tyburn. As for the explanation offered for the alternative burial sites, one could question whether in autumn 1658 Cromwell or his friends could foresee or seriously fear the return to power of desecrating and vengeful royalists. Perhaps we should listen to Jeremiah White, Cromwell’s close friend and personal chaplain. In 1664 Pepys put to him the allegation that the Protector had transposed the royal tombs in Westminster Abbey in order to secure his own remains from future molestation. White’s reply was simple and immediate – ‘he believes [Cromwell] never had so poor a low thought in him to trouble himself about [it]’.

Thus, despite all the fevered speculation, the numerous suggestions to the contrary, the colourful stories lovingly told and retold, the truth is probably quite prosaic and straightforward – that Cromwell’s body had been located in and exhumed from Westminter Abbey in January 1661, that, having been hanged during the day, on the evening of the 30 January his headless trunk was tossed into an unmarked pit at Tyburn and that his bones still rest somewhere in the former execution ground, now engulfed by the urban sprawl of London, beneath the Marble Arch junction or adjoining roads – Connaught Street and Square are sometimes suggested as possible spots. Meanwhile Cromwell’s head, which was with some difficulty removed by the executioner after the corpse had been hanged, has its own separate and fascinating tale to tell.

Having been removed in January 1661, Cromwell’s head was stuck on a pole and set up on the roof of Westminster Hall. This happened immediately, for Pepys noted its presence there in early February. It seems to have remained on display above Westminster Hall for many years, until sometime late in the seventeenth or early in the eighteenth century (various dates are suggested, ranging from as early as 1672 through to 1703) it was either deliberately removed or accidentally blew down in a storm and was carried off by a sentinel. Either way, during the eighteenth century it became a rather undignified collector’s item, passing through a number of private hands, though occasionally being put on wider or public display. In 1815 it was sold to Josiah Henry Wilkinson, who had the head examined and its authenticity analysed, before coming to the conclusion that it was, indeed, that of Oliver Cromwell. Now known generally as the ‘Wilkinson head’, in part to distinguish it from various other skulls which were occasionally put forward as belonging to the late Lord Protector, the remains passed through several generations of the Wilkinson family. The head was minutely examined several times during the early and mid twentieth century, subjected to close medical examination, photographed from different angles, x-rayed, weighed and measured, compared with other human remains and with assorted likenesses of Cromwell and discussed in a variety of learned, academic papers. Some of these exercises proved inconclusive, but most tended to confirm the origins of the Wilkinson head and to conclude that the head was probably or certainly that of Oliver Cromwell. In March 1960, on the assumption that the head was genuine, the Wilkinson head was buried or rather immured in the ante-chapel of Sidney Sussex, Cambridge, the college which Cromwell had attended as an undergraduate in 1616-17. It rests there still, its precise location undisclosed but its presence recorded by an inscribed tablet nearby. In recent years the Master and Fellows of Sidney Sussex have expressed a strongly-held view that they wish the head to remain undisturbed and would not sanction its removal for renewed examination or reburial elsewhere.